A Systematic Review of the Literature Workplace Violence in the Emergency Department

1. Introduction

Workplace violence in healthcare is a global and highly prevalent problem; within the healthcare sector, emergency departments (EDs) are considered a high-hazard setting for workplace violence [1,2]. Workplace violence has been defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) [iii] (p. 4) as "any activity, incident or behaviour that departs from reasonable bear in which a person is assaulted, threatened, harmed, injured in the course of, or every bit a directly result of, his or her piece of work". Accordingly, workplace violence can exist of a physical or psychological nature [4,5]. Workplace violence can be categorised into four types based on its source: criminal intent, customer/client, worker-on-worker, and personal relationship. In the healthcare sector, violence perpetrated past customers or clients (in this case patients) is most common [half dozen]. Liu et al. [1] examined global prevalence rates of workplace violence caused by patients and visitors confronting healthcare workers in a meta-analysis. The global 12-calendar month prevalence in EDs was 31% (95% CI, 26%–36%) for physical violence and 62.three% (95% CI, 53.7%–seventy.8%) for nonphysical violence. Amongst employees in EDs of a large German infirmary, the nigh frequent forms of reported physical violence incidents (n = 2853) were belongings/clinging (22%), pinching (17%) and spitting (xvi%). For nonphysical violence incidents (due north = 15,126) these were grumbling (40%), shouting (nineteen%) and insulting (19%) [7]. In emergency principal healthcare clinics in Norway, 60% of 320 aggressive incidents were considered equally astringent (score of ≥ 9 on a scale from 0 to 21) [8]. In EDs, several factors converge that can contribute to the occurrence of tearing incidents. On the office of the patients, literature reviews describe booze and drug intoxication and mental illnesses equally important take chances factors [9,10,11]. Concerning the organization and staff in EDs, night shifts [ten,12], long waiting times for patients, high task demands of staff [xi,12] and an inadequate worker–patient relationship [eleven], increase the gamble of workplace violence. Experiences of workplace violence can have serious negative consequences for ED staff. Italian ED healthcare workers who had suffered incidents of violence reported effects on lifestyle, such equally sleep disorders and changes from social relationships to social isolation [13]. About 20% of 252 reported physical assaults in three EDs in the USA resulted in an injury [14]. ED staff who had suffered verbal abuse reported consequences on their mental health and well-being, such as irritation, anger, depression, anxiety, guilt, humiliation, feelings of helplessness and disappointment [11]. In add-on, exposure to nonphysical violence can significantly impact symptoms of exhaustion, secondary traumatic stress and compassion satisfaction in ED staff [xv]. Negative consequences tin also affect the organisation. The experience of workplace violence amongst ED nurses in the USA was related to experiences of negative stress, decreased work productivity, and the quality of patient care [xvi]. Therefore, prevention of workplace violence is of great importance, only measures are not nevertheless consistently implemented [17]. In a survey of nursing staff (northward = 105) in EDs of seven German language hospitals, 73% of the participants stated that they did non feel prophylactic at their workplace and that they were non well prepared for incidents of violence [eighteen].

Prevention interventions tin can be categorised into prevention, protection and handling approaches. While treatment approaches aim to reduce the negative touch on of violent incidents, prevention and protection approaches proactively aim to reduce the adventure of violence or amend the handling of tearing incidents [4]. The latter 2 can be implemented at an environmental, organisational and/or behavioural level. Co-ordinate to guidelines on the prevention of workplace violence in the healthcare sector, ecology changes could be implemented in the class of controlled access, good lighting, clear signs, comfortable waiting areas, alarm systems, surveillance cameras and the removal or securing of weaponisable furniture. At an organisational level, it is farther recommended to ensure that staffing is sufficient and adequate, to avoid having staff piece of work lonely, to broadcast information on patients, to practice open advice, and to amend piece of work practices. Finally, interventions possible at a behavioural level include training of staff members, superiors and managers on policies and procedures, de-escalation and self-defence techniques [4,5,19]. Nonetheless, the feasibility and effectiveness of interventions for prevention in EDs, e.g., in terms of how they reduce violent incidents and ameliorate the knowledge of ED staff, and help them to feel safety and at ease, are yet unclear [12,18]. This is why, recent literature has been systematically reviewed and summarised.

This systematic review aims to summarise the existing evidence from evaluation studies on the prevention of patient-on-employee violence and aggression in EDs, where the purpose of the studies was to reduce the frequency of violent incidents, to increase knowledge, skills, or awareness related to violent incidents, or to help ED staff feel safer and more at ease.

2. Materials and Methods

The conduct and description of this systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [20]. Prior to conducting the review, a detailed study protocol was prepared on the procedures and methods planned. The protocol is bachelor in German language and tin exist obtained from the corresponding writer on request.

two.1. Eligibility Criteria

The screening and option of studies was based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria co-ordinate to the PIO scheme (population, intervention, upshot), supplemented by criteria for exposure and study design and by specified report characteristics (publication blazon, date, study region). Table 1 provides an overview of the eligibility criteria. The presence of a command group was not a requirement for inclusion in this review. Nosotros included studies that had an external command grouping, a pre/post pattern, where participants were their own controls, and also studies that had no controls. Moreover, no studies were excluded on the basis of language.

two.2. Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted in the electronic databases MEDLINE (via PubMed), Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CINAHL and PsycINFO on 14 September 2020. An update of the search was conducted on 31 May 2021. Databases were searched for entries dating from the twelvemonth 2010 onwards. The search string combined keywords concerning the population/occupation (due east.g., "health personnel"), the population/setting (eastward.thou., "emergency service*"), the exposure (e.g., "assailment*") and the intervention (eastward.1000., "instruction*"). The search string was first adult for MEDLINE and and then adapted to the other databases (Supplementary Tabular array S1). Additionally, reference lists of included studies and reviews on like topics were hand-searched for farther relevant studies.

2.iii. Study Selection

All records identified through the literature search were transferred to the literature management program EndNote and duplicates were removed. The screening of titles and abstracts for relevant studies was conducted by ane reviewer (TW). Unclear titles/abstracts were screened by another reviewer (CP) and discussed past both reviewers until consent for inclusion or exclusion was achieved. Full-text articles were screened independently past ii reviewers (TW and CP) using a standardised screening instrument, including the eligibility criteria for study pattern, publication blazon, written report region, study population, exposure, intervention and result. Studies that met all criteria were included in the review. Whenever the two reviewers came to differing conclusions almost inclusion or exclusion, these were resolved by discussion.

2.4. Data Extraction

Firstly, the characteristics of included studies were extracted by a reviewer (TW) using a standardised data course and verified by a second reviewer (CP). The extracted information included first author, publication date, study region, study design, study setting and population, intervention description, follow-upward period, and primary and secondary event parameters. Secondly, fundamental findings of the included studies were extracted past i reviewer (TW) using a standardised Microsoft® Excel® spreadsheet. A 2d reviewer (CP) verified the accuracy of the extracted information.

2.5. Quality Assessment

A quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the Critical Appraisal Tools of the Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [21,22]. The Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies was used for most of the included studies [22]. It comprised 9 items with the four possible response categories being "yep", "no", "unclear" and "not applicative". Particular eight, originally asking for outcomes being measured in a reliable mode, was not applicable to most studies. Therefore, it was slightly adjusted to determine whether validated instruments were used. Three descriptive cross-exclusive studies were appraised using the Checklist for Prevalence Studies [21]. It also comprised nine items with the same four response categories. Ii appraisers independently assessed the quality of the studies (TW and CP). Differing conclusions were resolved past discussion. An overall score for each study was calculated by summing the number of "yes" responses. A score of ≤3 was considered as low quality, from 4 to 6 as moderate and ≥7 every bit high quality. No studies were excluded on the basis of methodological quality.

2.6. Synthesis of Results

The main characteristics of the included studies were analysed descriptively and summarised in a tabular array. A narrative summary of the key findings was provided. Information technology included a description of the different types of interventions and results on the main outcomes. Differences and similarities between studies were highlighted and methodological quality was considered. It was not possible to perform pooled analyses (meta-analyses) due to the large heterogeneity of the studies in terms of the interventions performed, survey instruments used and event parameters investigated.

3. Results

3.i. Report Choice

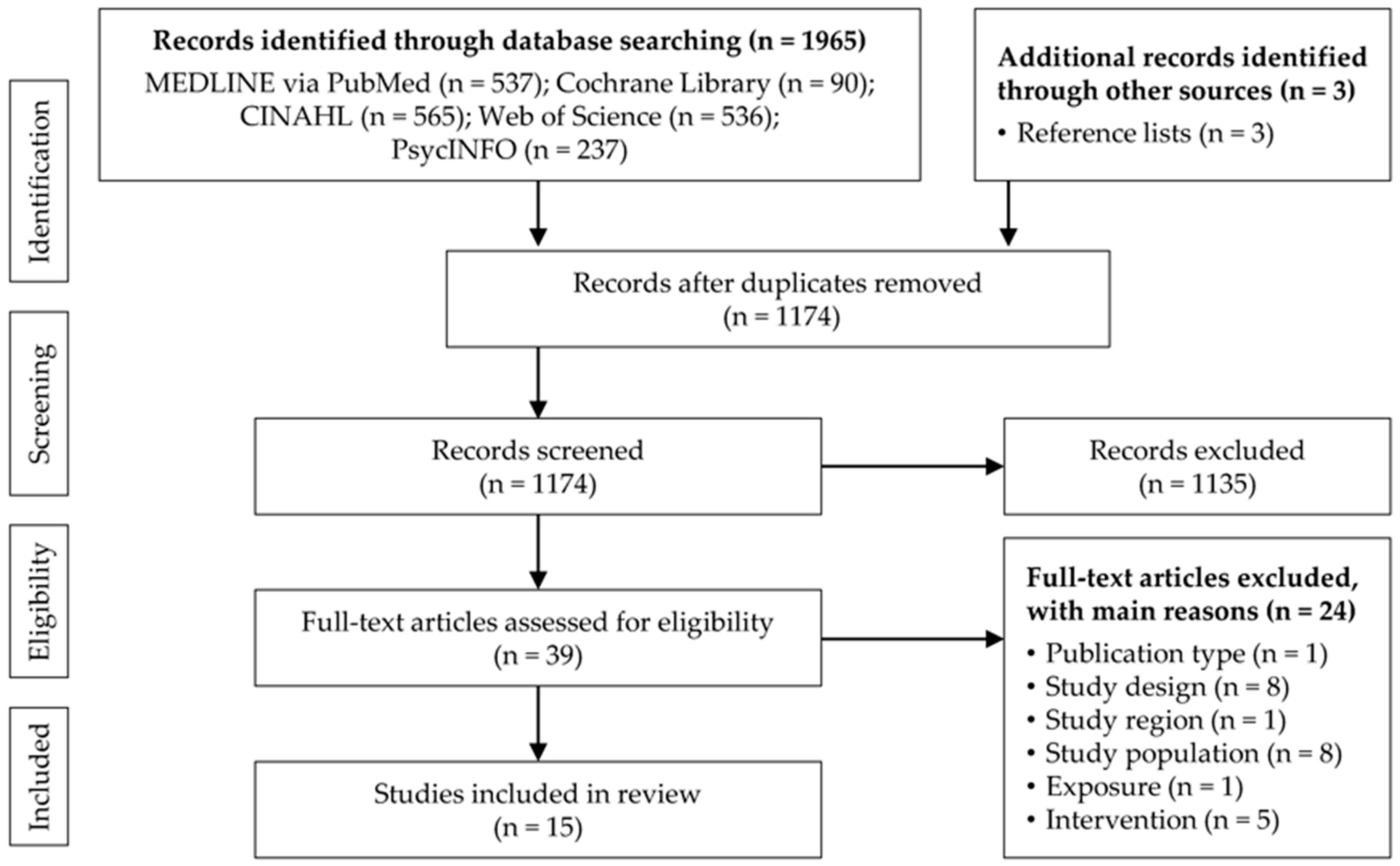

Overall, 1965 records were identified through the database search and three additional studies through the screening of reference lists. After duplicates were removed, 1174 titles/abstracts were screened and subsequently, 39 total-text manufactures were assessed for eligibility. Xv studies were included in the review (Figure 1).

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table two provides an overview of the characteristics of the included studies. Of the xv studies, ten were conducted in the Us [xiv,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], ii in Australia [32,33], two in French republic [34,35] and one in Deutschland [36]. V studies were published in each of the three time periods, from 2010 to 2013 [26,27,32,33,34], from 2014 to 2017 [14,23,25,28,31], and from 2018 to 2021 [24,29,30,35,36], respectively. Ten studies had a quasi-experimental design, about of them using pre- and post-tests [14,23,24,26,28,29,30,31,33] and ane identifying itself as an interrupted time-series study [35]. One was a mixed-methods study with its main component being a pre- and post-test survey [32]. One study described itself as an observational written report [25] and three were cross-sectional evaluation studies [27,34,36]. Eleven studies implemented behavioural interventions [23,24,25,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,36]. Four studies used multi-component approaches including behavioural, organisational and environmental interventions [14,27,30,35]. As an outcome mensurate, 3 studies examined knowledge attainment of participants through a test score [23,26,28], eight studies included self-reported noesis, confidence, ability, skills or attitudes of staff [23,24,29,thirty,31,32,33,36], four studies measured a change in violence incidence [14,25,30,35] and ii studies merely evaluated the satisfaction with or success of the intervention [27,34].

3.iii. Quality Cess

Iii studies were classified equally being of low [27,thirty,34], ten of moderate [23,24,25,26,28,29,31,33,35,36] and 2 of high quality [xiv,32] (see quality score in Table 2). Quasi-experimental studies most often lacked an contained control group, multiple pre/post measurements, a complete follow-up, an adequate description of those lost to follow-up or valid outcome measures. For the cantankerous-exclusive studies, a detailed description of the report subjects and setting, sufficient coverage of the identified sample, or the use of valid methods for the identification of the status, were most often not provided. Further detailed critical appraisal results are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S2 and S3).

Table ii. Characteristics of the included studies (northward = 15).

Table 2. Characteristics of the included studies (due north = 15).

| Reference, Country | Report Design | Setting | Study Size (northward), Population, Sex, Age | Comparison Group | Intervention | Follow-up Menses | Related Effect Measures | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball et al. (2015) [23], United states | Pre- and post-test written report | Suburban academic level I trauma middle | 93 4th-twelvemonth medical students during their 4-calendar week ED clerkship, 58.1% female, mean age: 26.8 years | Matched pre- and post-surveys; 30 students who did not scout video | 10-min video podcast covering learning objectives in violent person management | Pre-test: during the 4-week ED clerkship Post-test: at the final test | Cognition attainment (modify in test score), change in self-reported confidence in identifying and responding to a violent situation | 6/9 |

| Bataille et al. (2013) [34], French republic | Cantankerous-sectional, single heart evaluation study | Emergency intensive care unit of the general infirmary of Narbonne | 27 medical and paramedical employees, sex and age NR | N/A | Grooming with the principal objective of defusing a conflict situation (basics of conflict psychology, self-defense gestures and postures) | Due north/A | Satisfaction with the training | ii/9 |

| Buterakos et al. (2020) [24], USA | Quasi-experimental study with two phases | ED (level I trauma center for adults and level II trauma centre for paediatrics) in an urban hospital | Phase I: 25 nurses, 72% female, forty% 31–40 years Phase Two: 34 nurses, 76.v% female, historic period NR | Matched pre- and post-surveys | 5-min educational in-service training sessions and reinforcement posters on: phase I: importance of reporting; phase II: assertive de-escalation and self-protection | Phase I: baseline and one-month post-intervention Phase II: baseline and 2-month post-intervention | Increase in the reporting of assaults, increase in nurses' confidence in de-escalation and ability to protect themselves during assaults | four/9 |

| Frick et al. (2018) [36], Germany | Cross-sectional evaluation study | Acute intendance units (EDs, paediatric EDs and obstetrics) at the Charité Berlin | 110 staff members (92.3% nurses), sexual activity and age NR | Northward/A | Three 8-h days of in-house de-escalation grooming past multipliers | N/A | Cocky-cess and application of skills after the training (detection of warning signals, verbal de-escalation, defence and escape techniques, dealing with provocative behaviour) | 4/9 |

| Gerdtz et al. (2013) [32], Australia | Mixed methods, multisite evaluation written report (pre- and post-test survey and individual interviews) | Public-sector EDs in Victoria | Survey: 471 registered nurses and midwives, 86.6% female, 33.ane% 20–29 years Interviews: 28 nurse unit managers and trainers, 85.seven% female, age NR | Matched pre- and mail service-surveys | Management of Clinical Aggression–Rapid Emergency Section Intervention (MOCA-REDI) plan (45 min. in-service session, train-the-trainer model) | Survey: before and six–8 weeks afterward grooming Interviews: eight–x weeks afterwards training | Survey: staff attitudes about the causes and management of patient assailment Interviews: staff perceptions of the impact of the training | 7/9 |

| Gillam (2014) [25], USA | Single-phase observational written report | Primary ED of an acute tertiary care hospital | ED staff (n, sex and age NR) | Monthly code majestic activeness | 8-h nonviolent crunch intervention training plan for ED staff | November 2012 to October 2013 | Change in lawmaking royal incidence (violent events that initiate emergency response by infirmary security squad) in terms of completed training | 5/nine |

| Gillespie et al. (2012) [26], USA | Quasi-experimental report | 3 EDs (ane level I trauma centre, 1 urban ED, one suburban ED) in the Midwestern The states | 315 employees from the EDs (47.9% unlicensed assistive personnel), sexual activity and historic period NR | Matched pre- and post-surveys; comparison: web-based learning only (n = 95) vs. hybrid group (n = 220) | Educational programme: spider web-based learning programme (units 1–3) and web-based/classroom-based hybrid learning plan (units 1–3 and unit of measurement iv) | Pre-test: prior to unit 1 Post-test: following completion of the programme with or without unit 4 | Cognition attainment (change in test score) | 4/ix |

| Gillespie et al. (2013) [27], U.s. | Cross-sectional evaluation report using action research | Three EDs (ane level I trauma eye, one urban ED, one suburban ED) in the Midwest The states | 53 ED employees (66% nurses), sex and historic period NR | N/A | (1) Walk-throughs with recommendation of environmental changes (2) policies and procedures for each hospital (3) online and classroom training | Northward/A | ED employees' rating of the programme'south do good, ease of implementation, level of commitment and importance of (sub)components | i/9 |

| Gillespie et al. (2014) [28], U.s. | Quasi-experimental, repeated measures study | Two paediatric EDs (ane community based, i level I trauma center) and one developed/paediatric ED (university-affiliated level I trauma centre), Midwest United states | 120 employees (71.vii% registered nurses), 86.7% female, age NR | Matched pre- and post-surveys | Hybrid workplace violence educational plan with online and classroom components | Time 1: prior to online modules Time 2: after completing online modules Time three: 6 months after classroom module | Noesis attainment and retention on preventing, managing, and reporting incidents of workplace violence (change in test score) | vi/9 |

| Gillespie et al. (2014) [14], United states of america | Quasi-experimental, repeated measures study | 3 EDs (one level I trauma center, one urban third intendance ED, ane community-based suburban ED) | 209 ED employees (56% nurses), 71.3% female person, mean age: 37.3 years | Three comparison site EDs | (ane) Walk-throughs with recommendation of environmental changes (2) policies and procedures for each hospital (3) online and classroom preparation | Monthly survey for nine months before the intervention and 9 months after the intervention | Reduction of the incidence of physical assaults and threats confronting ED employees by patients and visitors | 8/9 |

| Hills et al. (2010) [33], Australia | Pre- and mail-test study | Rural hospital EDs and wellness services in New Due south Wales | 55 (pre-survey)/33 (mail-survey) ED and Mental Wellness Service clinicians and Health and Security Assistants, sexual activity and age NR | Unmatched pre- and mail-surveys | 24-calendar week online learning programme including i.a.: assessing, identifying and managing risk and rubber, therapeutic communication and de-escalation skills | Survey: earlier and after completing the programme | Knowledge and skill development (perceived self-efficacy and confidence in dealing with aggressive behaviour and mental health issues) | 4/ix |

| Krull et al. (2019) [29], USA | Pre- and mail service-examination study | ED in the Upper Midwest region of the United states | 96 interprofessional ED staff (55% registered nurses), 74% female, historic period NR | Matched pre- and post-surveys | Individual computer-based and simulation training (20-min patient scenario, 25-min debriefing session) on de-escalation techniques and restraint awarding | Pre- and post-survey directly earlier and after the simulation preparation | Knowledge, skills, abilities, confidence, and preparedness to manage aggressive or violent patient behaviour | 6/9 |

| Okundolor et al. (2021) [thirty], Us | Pre- and postal service-test written report and retrospective review of incident study system | Psychiatric ER of the ED of a large, urban, public, academic hospital in Los Angeles | 42 psychiatric ER nursing staff, sex and age NR | Matched pre- and post-surveys and monthly incidents | (ane) behavioural response team drills (2) pre-shift conference (3) screening for patients' adventure for violence (4) posting signage (5) countermeasure interventions (half-dozen) post-assault debriefing (seven) post-assail support | Survey: earlier, during and after the interventions Tape review: monthly from May 2016 to September 2018 | Perceived self-efficacy in managing patients with a propensity for violence, number of physical assaults (with harm scores ≥five) on staff per month | 3/9 |

| Touzet et al. (2019) [35], France | Single-centre, prospective interrupted fourth dimension-series study | Developed ophthalmology ED of an urban academy infirmary in the Rhône-Alpes region of France | 30 healthcare workers (23% nurses, 23% residents), sexual activity and historic period NR | Pre–post analysis | (one) computerised triage algorithm (2) signage (3) messages broadcast in waiting rooms (4) mediator (v) video surveillance | 3-month pre-interventional menstruum, 3-month grooming menses and 12-month implementation menstruation of the program | Violent acts committed by patients or persons accompanying them against healthcare workers, other patients or persons accompanying patients among all admissions | v/nine |

| Wong et al. (2015) [31], USA | Pre- and mail service-test study | ED | 106 ED staff members (41% nurses), 58% female, 34% 26–30 years | Matched pre- and post-surveys | Simulation-enhanced interprofessional curriculum (30-min lecture, ii simulation scenarios, structured debriefing) | Pre- and postal service-survey directly before and after the form | Staff attitudes towards management of patient aggression | vi/9 |

3.iv. Results on Behavioural Interventions

3.four.1. Online Training Programmes

Two studies implemented online training and measured the result on staff noesis, skills and conviction in identifying and dealing with violent situations. Ball et al. [23] provided a x-min video podcast on violent person management to fourth-year medical students during their emergency medicine clerkship. They found a meaning improvement in knowledge examination scores after watching the podcast (mean deviation 1.77, 95% CI 1.42–2.13, p < 0.001, n = 93) and college test scores compared to xxx students who did not watch the podcast (hateful 5.82 ± one.38 vs. 4.13 ± 1.48, p < 0.001). In add-on, the proportion of students feeling confident in responding to a vehement person significantly increased (xv.0% vs. 47.iii%, p = 0.00) but not the proportion of those feeling confident in identifying a potentially violent person (48.4% vs. 80.9%, p = 0.21).

Hills et al. [33] implemented a 24-week online learning program, due east.grand., on take chances and prophylactic and de-escalation skills, in general hospital EDs and Mental Health Services, and found a pregnant improvement in perceived self-efficacy in dealing with ambitious behaviours of clients (mean 21.v ± 6.0, n = 55 vs. 26.three ± iii.9, n = 33, p < 0.001). A further significant improvement was seen in confidence for deciding if a person might be at take chances of harming others (mean four.v ± 1.ii vs. 5.6 ± 0.8, p < 0.001).

3.4.ii. Classroom Grooming Programmes

Six studies reported on interactive classroom or short in-service training sessions, which all included components on de-escalation and/or self-defence force techniques. Buterakos et al. [24] used short in-service sessions and reinforcement posters on reporting, de-escalation and self-protection. They found no significant difference in the confidence of 34 participants regarding de-escalating an ambitious patient before and later the intervention (Z = −1.022, p = 0.27). Gerdtz et al. [32] also implemented an in-service grooming session via a train-the-trainer model on de-escalation techniques and effective communication skills for the prevention of patient aggression. They found only limited evidence (statistically significant changes only in i fifth of their items tested) for changes in attitudes well-nigh the causes and management of aggression. Interviewed managers/trainers did, however, perceive a positive impact on the manner staff worked to preclude patient aggression. Gillam [25] examined the effect of an viii-h nonviolent crisis intervention grooming session on the incidence of violence in one hospital ED. The grooming included techniques to de-escalate potentially fierce situations and to avoid injuries. The writer found a pregnant decrease in fierce events that initiated emergency responses by the hospital security team when more staff were trained in the previous 90–150 days, but non when the time of grooming was further dorsum. Wong et al. [31] adult an interprofessional curriculum including case-based simulations that incorporated de-escalation and cocky-defence techniques, team-based approaches, the awarding of concrete restraints and medication. Participants' attitudes towards patient aggression factors significantly improved from pre- to post-intervention (all p < 0.01), except for the clinical management of aggression (p = 0.54). The other two studies did non provide a comparing over time. Bataille et al. [34] implemented preparation with the master objective of defusing a conflict situation. The training was satisfactory and clear to all 27 participants, with 96% feeling that they had learned new things; all wanted to continue and expand the training. Frick et al. [36] evaluated a iii-day in-house de-escalation preparation programme using multipliers. Afterwards the training, skills were rated every bit "very high" or "high" by 56.5% for the detection of warning signals, by 48.1% for verbal de-escalation, by 25.2% for defence/escape techniques and by 44.4% for dealing with provocative behaviour (of n = 110).

three.4.3. Hybrid Training Programmes

3 studies examined the effects of hybrid educational interventions on ED staff knowledge on preventing and managing workplace violence. In two studies, Gillespie et al. [26,28] implemented an educational programme consisting of web-based and classroom-based learning units. At that place was a meaning increase in knowledge among participants of the spider web-based unit (t = five.008, p < 0.001, n = 95) and also among participants of the web-based and classroom-based unit (t = 9.629, p < 0.001, north = 220) compared to scores before the intervention. The knowledge attainment did not differ significantly betwixt both groups [26]. Gilliespie et al. [28] all the same plant a significant increment in cognition on preventing, managing and reporting incidents of workplace violence at vi months after completion of the full programme (F = 53.454, p < 0.001). Krull et al. [29] provided computer-based training followed by simulation training on de-escalation techniques and restraint application. ED staff perceived their knowledge, skills, ability, confidence and preparedness to manage aggressive patient behaviour to be significantly higher subsequently the training (all p < 0.001).

three.5. Results on Multicomponent Interventions

Iv studies used multicomponent programmes, including behavioural, organisational and ecology interventions, to reduce the number of exact violent events, threats and/or physical assaults against ED staff. In two studies, Gillespie et al. [fourteen,27] examined the furnishings of a programme that included walk-throughs to identify ecology risks and implement site-specific changes, the conception of best do policies and procedures, and online and classroom grooming for workplace violence prevention and direction. The program was rated by employees (n = 53) as moderately beneficial. The programme subcomponents seen equally most important were surveillance and monitoring, environmental changes and classroom education [27]. In addition, there was a meaning decrease in the incidence of physical assaults and threats against ED workers in the intervention EDs from pre- to mail-intervention. However, this was too observed for the comparing grouping without the intervention [fourteen]. Okundolor et al. [30] examined the outcome on the number of physical assaults on staff, of a multifaceted intervention including behavioural response squad drills, pre-shift briefing, screening for patients' adventure for violence, the posting of signage, countermeasure interventions and post-assault debriefing and support. They observed a 75% decrease of assaults between July 2017 and June 2018, as compared to the aforementioned time period in the previous yr. Touzet et al. [35] implemented a programme including a computerised triage algorithm, signage, messages broadcast in waiting rooms, the presence of a mediator and video surveillance. The number of self-reported acts of violence significantly decreased from 24.8 per one thousand admissions (95% CI 20.0–29.5) preintervention, to 9.5 per yard (95% CI 8.0–10.9) in the intervention flow (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This systematic review summarises the current research on workplace violence prevention interventions aiming to reduce the frequency of trigger-happy incidents in EDs or increase ED staff noesis, skills or conviction to manage aggressive patient behaviour. A total of 15 studies published since the year 2010 were identified. Eleven of them examined behavioural interventions in the form of classroom, online or hybrid training programmes on de-escalation skills, violent person management or cocky-defense techniques. Four studies included not merely an educational component, but also organisational and ecology interventions in the ED. Most of the studies observed a positive touch on of their intervention on the frequency of violent incidents or the preparedness of ED staff to deal with violent situations. Notwithstanding, due to the limited number of studies, heterogeneity of methods and the express methodological quality of studies, this result will need to be verified in future research.

In their review of the literature published betwixt the years 1986 and 2007 on interventions to reduce workplace violence against ED nurses, Anderson et al. [37] saw a paucity of inquiry evaluating such interventions and formulated a stiff need for further investigations. As shown by the present review, simply fifteen studies were identifiable in this regard since 2010. Of them, only ii were assessed as high-quality studies with a low risk of bias.

Almost studies examined behavioural interventions, more precisely training and didactics. Of them, two studies found no [24] or just very limited prove [32] for a positive effect of their intervention on the conviction and attitudes of staff regarding de-escalating and managing assailment. Both had examined short (5 and 45-min) in-service grooming sessions. It could exist concluded that longer training sessions are required to achieve a positive touch on staff confidence. Positive furnishings of short training sessions (e.1000., a ten min video podcast) were observed for knowledge attainment through a test score [23]; all the same, this does non imply that staff could likewise handle an aggressive situation better or feel well prepared to do so. In improver, it could be useful to implement frequent and regular repetitions of training. Gillam [25] recommended biannual grooming, equally she observed a decrease of violent events only when more than staff had been trained in the previous ninety–150 days and non for longer fourth dimension periods before that. Apropos the class of educational training, it can be noted that online, classroom equally well as hybrid programmes were identified in this review, and positive effects were observed past studies for all iii forms. In general, online programmes accept the advantage of beingness more flexible in terms of time and pace. On the other mitt, classroom programmes allow for the application of interactive exercises, which can brand learning, e.g., of de-escalation or self-defense techniques, more effective [38].

Anderson et al. [37] already noted that organisational and environmental issues in EDs cannot exist resolved through training interventions. In Deutschland, it is legally required that occupational wellness and safety measures at a behavioural level are subordinate to measures at an environmental and organisational level (§ 4 ArbSchG). Guidelines on violence prevention in healthcare besides as contempo studies developing frameworks for occupational violence based on the experiences of ED staff, also recommend comprehensive multidimensional approaches [4,39,40]. Three such comprehensive approaches have been identified through this review, all of which showed positive effects on the frequency of vehement incidents [14,30,35], but not an advantage over the external comparison group [14]. Similarly, a former systematic review institute preliminary show for ecology modifications (e.g., specialised behavioural rooms and security upgrades) for astute behavioural disturbance direction in EDs, merely no prove from controlled studies [41]. In this review, environmental and organisational preventive measures included, among other things, the implementation of signage, policies and procedures, video surveillance and screening for patients' risk for violence. The use of hazard assessment tools for screening patients was too suggested by ED staff in a survey on interventions for occupational violence [39]. In an Australian ED, the implementation of such a tool to place 'at hazard' patients, including a response framework, significantly reduced unplanned violence-related security responses [42]. Cabilan et al. [39] developed a framework for planning occupational violence strategies. As environmental prevention strategies, they recommended, to provide a security presence and duress alarms, to improve staffing and to limit the number of visitors.

iv.1. Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review included merely research articles and no specific search was conducted to identify gray literature, so it is possible that some studies might take been missed. Apart from this, the review provides a comprehensive flick of current workplace violence prevention interventions in EDs through extensive database searching and the inclusion of different report languages. When interpreting the results and conclusions, it should be considered that studies with low quality scores were not excluded from this review. Some of the included studies had shortcomings, east.g., by failing to include an external control grouping. Most studies did non include multiple measurements after the intervention, preventing conclusions from beingness drawn almost the long-term effects of the interventions. Some had a cross-sectional pattern and did non provide pre- and postal service-testing. No conclusions about causal relationships can be derived from these studies. In addition, most studies relied on self-reports of their participants when measuring outcome furnishings of the intervention, which can increase the risk of bias. Studies included in this review differed considerably in their applied methods, their consequence parameters and the instruments used to measure these. Therefore, information technology was not possible to pool data, which further limits the results of this systematic review.

iv.2. Implications

ED staff oftentimes experience exact and physical violence from patients and their relatives, which can significantly bear upon their wellness. Therefore, workplace violence prevention should be incorporated in emergency clinical care. While staff should be trained in de-escalation and self-defence techniques, organisational and ecology improvements should likewise exist implemented in EDs. A hazard assessment, e.g., based on a walk-through, can help to identify specific needs and find appropriate preventive measures for the private ED [4]. For measures to be successful, it is recommended to involve other stakeholders such equally security personnel also as hospital and ED management to proceeds leadership support [27]. Equally shown by this review, preventive measures can have positive effects on the frequency of tearing incidents and staff noesis, skills and confidence to handle critical situations. Implemented interventions should, however, be evaluated for their effectiveness. In this regard, more research is needed to examine the effects of workplace violence prevention interventions. Future studies should have care to use comparable consequence measures, include an external command grouping and examine long-term effects of interventions by conducting multiple measurements over a longer period of time after the intervention.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review provides an overview of current research on workplace violence prevention interventions in hospital EDs. The findings revealed that the included studies mostly showed some positive impact of behavioural and multidimensional interventions on the reduction of violent incidents from patients towards ED staff or the preparedness of staff to deal with vehement situations, although the evidence is still sparse. Further studies are needed, that are of high methodological quality and that consider environmental and organisational interventions in detail, equally these have rarely been studied so far. This would exist an important contribution to promote the introduction of workplace violence prevention interventions in EDs and increase knowledge on the effectiveness of specific measures.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph18168459/s1, Tabular array S1: Search string for MEDLINE (PubMed), Tabular array S2: Critical appraisal results of the included studies using the JBI Disquisitional Appraisement Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies, Table S3: Disquisitional appraisal results of the included studies using the JBI Disquisitional Appraisal Checklist for Prevalence Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.W., C.P., A.N. and A.S.; methodology, T.W., C.P. and A.Southward.; formal analysis, investigation, resources, T.Due west. and C.P.; writing—original draft training, T.W.; writing—review and editing, C.P., A.Due north. and A.S.; visualisation, T.W.; supervision, A.N. and A.S.; project administration, T.W.; funding acquisition, T.Due west., C.P., A.N. and A.South. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This piece of work was supported by the High german Social Accident Insurance for the Health and Welfare Services (BGW), a non-profit organisation that is part of the national social security organization based in Hamburg, Germany.

Institutional Review Lath Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicative.

Data Availability Argument

No new data were created or analysed in this report. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of involvement. The funders had no function in the design of the study; in the drove, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the determination to publish the results.

References

- Liu, J.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, 50.; Dwyer, R.; Lu, Thou.; Yan, Due south.; Sampson, O.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.Due east.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, 10.10. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: A quantitative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour System (ILO). Code of Practise ON Workplace Violence in Services Sectors and Measures to Combat This Phenomenon; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107705.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Wiskow, C. Guidelines on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector—Comparing of Major Known National Guidelines and Strategies: United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, USA; ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WV_ComparisonGuidelines.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- International Labour Role (ILO); International Council of Nurses (ICN); World Wellness Organization (WHO); Public Services International (PSI). Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Wellness Sector; ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Plan on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/workplace/en/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- The University of Iowa Injury Prevention Inquiry Center (IPRC). Workplace Violence: A Report to the Nation; The Academy of Iowa: Iowa City, Iowa, 2001; Bachelor online: https://iprc.public-health.uiowa.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/workplace-violence-written report-1.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Lindner, T.; Joachim, R.; Bieberstein, S.; Schiffer, H.; Mockel, M.; Searle, J. Aggressive and provocative behaviour towards medical staff. Results of an employee survey of the emergency services at the Charite-Academy Medicine Berlin. Notfall Rettungsmed. 2015, 18, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, K.Due east.; Morken, T.; Baste, V.; Rypdal, Yard.; Palmstierna, T.; Johansen, I.H. Characteristics of aggressive incidents in emergency chief health care described by the Staff Observation Aggression Calibration—Revised Emergency (SOAS-RE). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, twenty, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabilan, C.J.; Johnston, A.N. Review commodity: Identifying occupational violence patient hazard factors and risk assessment tools in the emergency section: A scoping review. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2019, 31, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikathil, South.; Olaussen, A.; Gocentas, R.A.; Symons, Due east.; Mitra, B. Review commodity: Workplace violence in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta analysis. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2017, 29, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Ettorre, G.; Pellicani, V.; Mazzotta, K.; Vullo, A. Preventing and managing workplace violence confronting healthcare workers in Emergency Departments. Acta Biomed. 2018, 89, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, T.; Hachenberg, T. Violence in the Emergency Medicine (Emergency Rescue Service and Emergency Departments)—Current State of affairs in Germany. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notfallmed. Schmerzther. 2019, 54, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavò, Thou.; La Torre, F.; Sestili, C.; La Torre, Chiliad.; Fioravanti, Thousand. Work Related Violence Equally A Predictor Of Stress And Correlated Disorders In Emergency Section Healthcare Professionals. Clin. Ter 2019, 170, e110–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, 1000.L.; Gates, D.M.; Kowalenko, T.; Bresler, Southward.; Succop, P. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention to reduce physical assaults and threats in the emergency department. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2014, twoscore, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, D.; Henry, Yard. The relationship between workplace violence, perceptions of safe, and Professional person Quality of Life among emergency department staff members in a Level 1 Trauma Eye. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 39, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, D.M.; Gillespie, G.L.; Succop, P. Violence confronting nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nurs. Econ. 2011, 29, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frick, J.; Slagman, A.; Lomberg, 50.; Searle, J.; Mockel, M.; Lindner, T. Security infrastructure in German emergency departments. Results from an online survey of DGINA members. Notfall Rettungsmed. 2016, xix, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuffenhauer, H.; Güzel-Freudenstein, G. Violence towards nursing staff in emergency departments. ASU Arb. Soz. Umw. 2019, 54, 386–393. [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers; U.Southward. Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/osha3148.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, half dozen, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, One thousand.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In JBI Manual for Show Synthesis; Aromataris, East., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Commonwealth of australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Ball, C.A.; Kurtz, A.G.; Reed, T. Evaluating Fierce Person Management Training for Medical Students in an Emergency Medicine Clerkship. Southward. Med. J. 2015, 108, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buterakos, R.; Keiser, G.M.; Littler, S.; Turkelson, C. Report and Prevent: A Quality Improvement Project to Protect Nurses From Violence in the Emergency Section. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 46, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, Due south.W. Irenic crisis intervention preparation and the incidence of violent events in a large infirmary emergency department: An observational quality improvement study. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2014, 36, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, G.50.; Gates, D.One thousand.; Mentzel, T. An educational programme to foreclose, manage, and recover from workplace violence. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2012, 34, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, G.L.; Gates, D.Thousand.; Mentzel, T.; Al-Natour, A.; Kowalenko, T. Evaluation of a Comprehensive ED Violence Prevention Program. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2013, 39, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Thou.L.; Farra, Due south.50.; Gates, D.Yard. A workplace violence educational program: A repeated measures study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2014, 14, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, West.; Gusenius, T.M.; Germain, D.; Schnepper, Fifty. Staff Perception of Interprofessional Simulation for Exact De-escalation and Restraint Awarding to Mitigate Fierce Patient Behaviors in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 45, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okundolor, Due south.I.; Ahenkorah, F.; Sarff, L.; Carson, N.; Olmedo, A.; Canamar, C.; Mallett, S. Zero Staff Assaults in the Psychiatric Emergency Room: Touch of a Multifaceted Operation Improvement Projection. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2021, 27, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.H.; Wing, L.; Weiss, B.; Gang, Chiliad. Coordinating a Team Response to Behavioral Emergencies in the Emergency Section: A Simulation-Enhanced Interprofessional Curriculum. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, xvi, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdtz, Chiliad.F.; Daniel, C.; Dearie, 5.; Prematunga, R.; Bamert, Grand.; Duxbury, J. The outcome of a rapid preparation program on nurses' attitudes regarding the prevention of aggression in emergency departments: A multi-site evaluation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, D.J.; Robinson, T.; Kelly, B.; Heathcote, Due south. Outcomes from the trial implementation of a multidisciplinary online learning programme in rural mental health emergency intendance. Educ. Health 2010, 23, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, B.; Mora, M.; Blasquez, Southward.; Moussot, P.East.; Silva, South.; Cocquet, P. Grooming to management of violence in hospital setting. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Reanim. 2013, 32, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzet, S.; Occelli, P.; Denis, A.; Cornut, P.L.; Fassier, J.B.; Le Pogam, M.A.; Duclos, A.; Burillon, C. Impact of a comprehensive prevention programme aimed at reducing incivility and exact violence confronting healthcare workers in a French ophthalmic emergency department: An interrupted fourth dimension-series study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Slagman, A.; Mockel, Thousand.; Searle, J.; Stemmler, F.; Joachim, R.; Lindner, T. Experiences of aggressive behavior in the emergency section later on the implementation of a de-escalation training. Second staff survey in the acute care at Charite—Universitatsmedizin Berlin. Notfall Rettungsmed. 2018, 21, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; FitzGerald, M.; Luck, L. An integrative literature review of interventions to reduce violence confronting emergency department nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 2520–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occupational Health and Safety Assistants (OSHA). Caring for Our Caregivers. Preventing Workplace Violence: A Road Map for Healthcare Facilities; U.S. Department of Labor: Washington, DC, Usa, 2015. Available online: https://world wide web.osha.gov/sites/default/files/OSHA3827.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Cabilan, C.J.; Eley, R.; Snoswell, C.L.; Johnston, A.Northward.B. What can we exercise most occupational violence in emergency departments? A survey of emergency staff. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrablik, Chiliad.C.; Lawrence, 1000.; Ray, J.One thousand.; Moore, M.; Wong, A.H. Addressing Workplace Safe in the Emergency Department: A Multi-Institutional Qualitative Investigation of Wellness Worker Assault Experiences. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, T.J.; Ivory, South.; Hutton, J. Managing Astute Behavioural Disturbances in the Emergency Department Using the Surroundings, Policies and Practices: A Systematic Review. Due west. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, xviii, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senz, A.; Ilarda, Eastward.; Klim, S.; Kelly, A.Yard. Development, implementation and evaluation of a procedure to recognise and reduce aggression and violence in an Australian emergency department. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2020, 33, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure ane. Flow chart of the written report selection process.

Figure ane. Flow nautical chart of the study selection process.

Table ane. Eligibility criteria for the screening and option of studies.

Table ane. Eligibility criteria for the screening and selection of studies.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Healthcare workers in infirmary emergency departments | |

| Exposure | Violence and assailment by patients and their relatives | Violence due to criminal intent and personal relationship, worker-on-worker violence, use of firearms |

| Intervention | Prevention or protection approaches in the form of environmental, organisational and behavioural (teaching and training) interventions | Interventions focusing on documentation, mail service-incident handling, pharmacologic sedation or physical immobilisation of patients |

| Outcome | Frequency of violent incidents, staff knowledge, skills/competencies or awareness, staff sense of well-being and safety | Outcome parameters related to patients |

| Written report pattern | Interventional studies (eastward.g., randomised and nonrandomised controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies); observational studies (e.1000., cohort studies, cross-sectional studies) | Instance studies, reviews |

| Publication type | Enquiry articles | Letters to the editor/commentaries, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations |

| Publication date | From ane January 2010 | |

| Study region | Europe, North America, Australia | Other continents |

| Publisher'southward Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Eatables Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/).

gonzalezpiten1961.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/16/8459/htm

0 Response to "A Systematic Review of the Literature Workplace Violence in the Emergency Department"

Post a Comment